Introduction

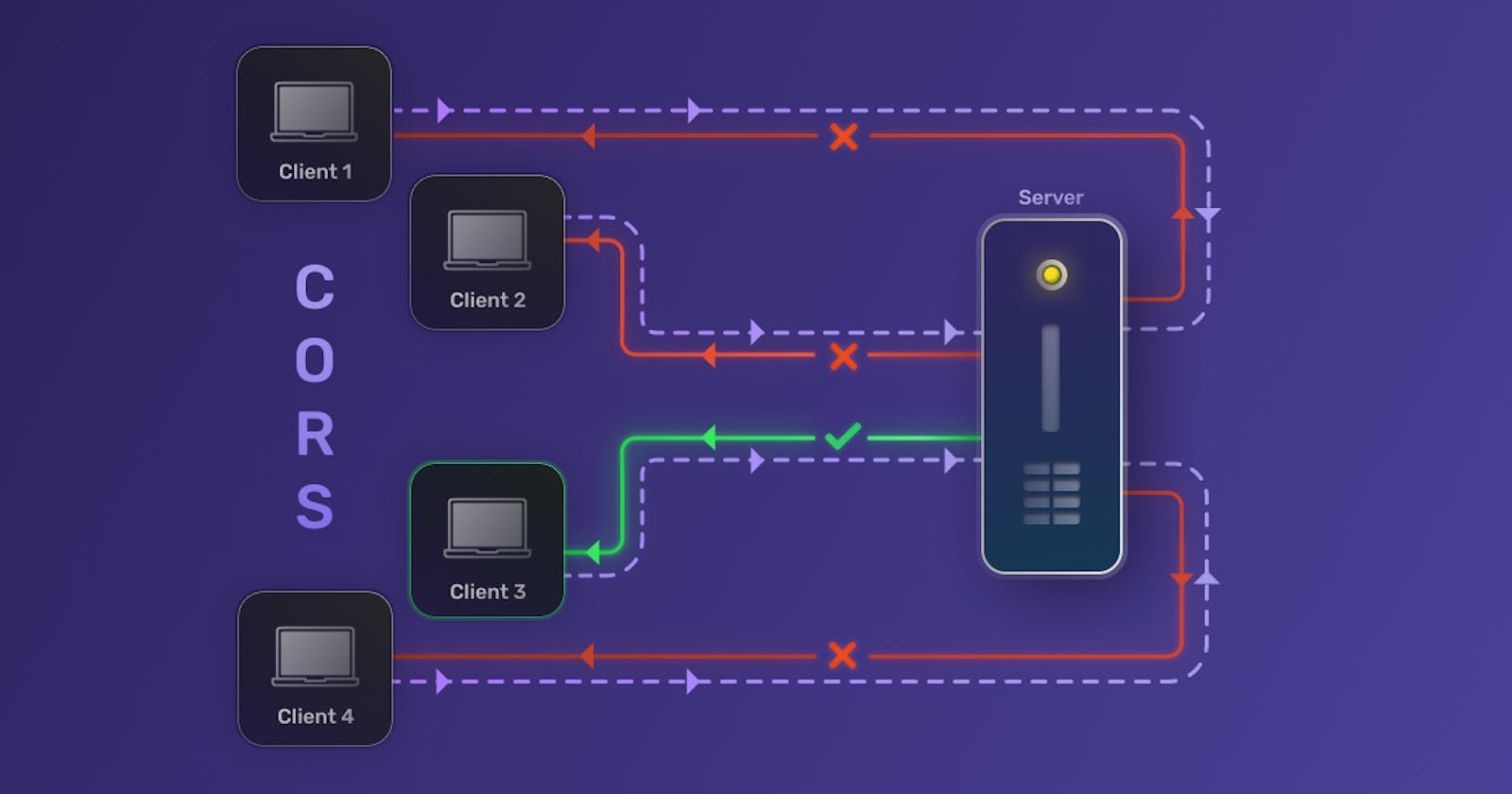

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) is a mechanism that supports secure requests and data transfers from outside origins (domain, scheme, or port).

For example, example.com uses a text font that's hosted on fonts.com. When visiting example.com, the user's browser will make a request for the font from fonts.com. Because fonts.com and example.com are two different origins, this is a cross-origin request. If fonts.com allows cross-origin resource sharing to example.com, then the browser will proceed with loading the font. Otherwise, the browser will cancel the request.

More concretely, CORS is a way for web servers to say "Accept cross-origin requests from this origin" or "Do not accept cross-origin requests from this origin".

This is important because cross-origin requests can be quite scary. I could be logged into my bank account and on visiting a malicious site, it could make requests to the bank's servers without my knowledge, and if CORS rules didn't exist, the request would go through - potentially changing or leaking my account information.

CORS is a protocol that defines the limitations of cross-origin requests. These limitations are enforced by our browsers. As a result, we can still make cross-origin requests while still maintaining a high level of security. By specifying which origins are allowed to make requests and which methods and headers are allowed, the browser makes sure that malicious actors can't retrieve sensitive data with cross-origin requests.

CORS History

CORS was invented to extend and add flexibility to the Same Origin Policy (SOP).

Same origin policy is essentially what the name suggests - resources can only be loaded from the same origin. Two origins are defined as the same if the protocol, port (if specified), and host are the same.

From a technical perspective, an origin can still request a resource from another origin, but the browser prevents the response from being readable.

However, sometimes, we still need to access resources from other origins - such as from fonts.com. That's where CORS comes in. CORS relaxes the Same Origin Policy by defining trusted or allowed origins, methods, and headers.

CORS preflight request

So now, let's get into the actual motion of what happens when requesting resources from another domain.

We've set up an example website at emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com where we can see the full CORS motion. This website calls an API on https://api-emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com. Even though both domains are subdomains of demo.supertokens.com, our browsers register them as different origins, and thus, CORS comes into the picture.

During sign in, if you open the browser's dev tools and see the network tab, you will see the preflight request being made. More specifically, the preflight request is an OPTIONS request made to our API domain with a couple of headers. Let's take a look at what happens when we click sign in -

OPTIONS /auth/signin HTTP/1.1

Host: api-emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com

Access-Control-Request-Method: POST

Access-Control-Request-Headers: content-type,fdi-version,rid

Origin: https://emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com

So that's our pre-flight request. Breaking this down, we have four key things to look at.

Host- The "host" of the resource that we're requesting. For us, that'sapi-emailpassword.demo.supertokens.comAccess-Control-Request-Method- The method of the request being made by our operation. This can be any of the HTTP request methods, includingGET,POST,PUT,DELETE, andCONNECT.Access-Control-Request-Headers- A comma-separated list of HTTP headers that would be used in the actual request.Origin- Where the request is coming from. For us, that'shttps://emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com

After getting this pre-flight / OPTIONS request, the API server sends over a pre-flight response. Here's our response from api-emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com.

HTTP/1.1 204 No Content

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com/

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET,PUT,POST,DELETE

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: content-type,rid,fdi-version,anti-csrf

Let's break this response down.

Access-Control-Allow-Origin- The origins that the API server has whitelisted. Notice that the value of this is the same as our website domain. This tells the browser that the server expects requests from this client.Access-Control-Allow-Credentials- The server telling us whether the actual request can include cookies in it, or that the response of the actual request can set-cookies. In our case, cookies refer to the session tokens of the user, which act as the credentials of the user once they're signed in.Access-Control-Allow-Methods- A comma-separated list of HTTP methods that the API domain allows for cross-origin requestsAccess-Control-Allow-Headers- A comma-separated list of HTTP headers that the API domain allows for cross-origin requests

The browser then takes this response from the API server to determine if the actual request should be sent. If the response from the API doesn't include the requested origin, methods, or headers from the preflight request, then the browser will not send the actual request.

CORS actual request

If the response from the API includes the requested origin, it's time to send the actual POST request to sign in.

POST /auth/signin HTTP/1.1

Host: http://api-emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com/

content-type: application/json

fdi-version: 1.15

rid: emailpassword

Content-Length: 92

Origin: https://emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com/

Note that the origin and the headers that are sent (fdi-version, rid, content-type), are whitelisted by the server, and the browser knows this because of the pre-flight response.

Now let's take a look at the response from the server.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://emailpassword.demo.supertokens.com/

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

front-token: ...

Access-Control-Expose-Headers: front-token, id-refresh-token

Set-Cookie: ...

Here, we get the response from the server with cookies and tokens that allows us to proceed with the sign-in operation. One thing to note is that compared to our pre-flight, we now also have an additional Access-Control-Expose-Headers header.

Access-Control-Expose-Headers- The server indicating which response headers are available for the scripts running in the browser. Interestingly, the reason this exists is not because of security, but because of backward compatibility to when CORS did not exist.

With this, we've now completed our first pre-flight request/response as well as our actual request/response for signing in!

Wildcards in CORS

One common mistake in configuring CORS is around the use of wildcards. Often, developers will elect to use the wildcard, *, when defining the origins, methods, or headers allowed with CORS.

While wildcards will work for simple requests (requests without HTTP cookies or HTTP authentication information), requests with credentials will often encounter a CORS not authorized error.

That's because in requests with credentials (cookies), the wildcard is treated as the literal method name or origin name "*" without special semantics. This occurs both in Access-Control-Allow-Origin and Access-Control-Allow-Methods, and some browsers like Safari simply don't have support for wildcards at all.

All in all, it's good hygiene to avoid the wildcard and use a comma-separated list when configuring CORS.

CORS vulnerability

When configured improperly, CORS can lead to major vulnerabilities. Below, we'll list a couple of common issues when configuring CORS.

Mishandling origin whitelist

One of the easiest mistakes to make when implementing CORS is mishandling the origin whitelist. When whitelisting origins, it's often easy to do simple matches with URL prefixes or suffixes, or using regular expressions. However, this can lead to quite a few issues.

Let's say that we grant access to all websites with the suffix whitelisted-website.com. This makes it easy for us to grant access to api.whitelisted-website.com.

But an attacker could use a website such as maliciouswhitelisted-website.com and gain access.

The best approach here to avoid potential abuse is to explicitly define origins on the whitelist for sensitive operations when implementing CORS - for example, specify the strings "https://whitelisted-website.com" and "https://api.whitelisted-website.com" which will grant access to only these domains.

Requests with null origin

Another common misconfiguration is whitelisting origins with the value null. Browsers might send the value null in the origin header in situations such as:

- Request with file

- Sandboxed cross-origin requests

In this case, an attacker can use various tricks to generate a request containing the value null as the origin which is whitelisted in our configurations. For example, the attacker could use the following sandboxed iframe exploit -

<iframe src="data:text/html" sandbox="allow-scripts allow-top-navigation allow-forms allow-same-origin">

function reqlistener() {

console.log(this.responseText)

}

var req = new XMLHttpRequest();

req.onload = reqlistener;

req.open("GET", 'vulnerable.com/sensitive', true);

req.withCredentials = true;

req.send();

</iframe>

Conclusion

We hope this article helps you understand the basic tenets behind CORS as well as some common pitfalls when implementing CORS.

SuperTokens is building open-source user authentication. We help companies manage authentication nuances, including handling CORS when calling an authentication server. If you encounter CORS related issues when implementing SuperTokens, head over to our docs to debug common issues or ask us directly on our Discord!